Even though Dominique Bellegarde was not breastfed as an infant herself, she has successfully nursed four out of her five children. She was able to do so, she says, because she had the support of her mother-in-law, who raised her children in a large, supportive community of women in Haiti.

“Her history of what she went through with nursing really helped guide me and keep me going,” says Bellegarde.

In contrast, Bellegarde’s birth mother immigrated from Haiti to the U.S. at 21 years old. When she had children soon after, she tried to nurse, but she had difficulty with it and opted for formula instead. In Haiti, she had been taken out of school to help her family financially, Bellegarde notes, and in Boston, she knew only a few people and wasn't surrounded by other nursing mothers.

The impact of social support and community know-how on breastfeeding success was clear to Bellegarde from her own family's experience, and she has paid forward what she learned from her mother-in-law to her sister, sitting with her in the apartment one floor down from her own and coaching her while she nursed her three children.

“I love helping people," Bellegarde says. "It has always been my calling, ever since I was young.”

Bellegarde has shared her knowledge and lived experience even more widely as a certified lactation counselor (CLC) with the Boston Breastfeeding Coalition, which was founded in 2016 and offers nine free breastfeeding support groups (known as "baby cafés") at various locations across the city, staffed by volunteers and certified lactation professionals.

The coalition's goals are bigger than just the baby cafes. An initiative of Boston Medical Center's Vital Village Network, the coalition aims to address historical disparities in breastfeeding rates by increasing access to breastfeeding education and support for mothers. Through a comprehensive training, continuing education, and mentorship program, it is also providing career pathways for individuals like Bellegarde who want to become professional lactation consultants — a career that can command significant salaries and one that white women have predominated.

“Our whole work is about building the capacity of local communities," says Erica Pike, communications and policy manager at the Vital Village Network. "There's so much strength already there. There [are] families who have successfully breastfed. How can we build on those successes to reach some of these larger goals?”

Addressing breastfeeding disparities

Breastfeeding in the first year of life is associated with better health outcomes for the baby, including a stronger immune system, and also better outcomes for the mother. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that mothers exclusively breastfeed their children for the first 6 months, and continue breastfeeding until 12 months.

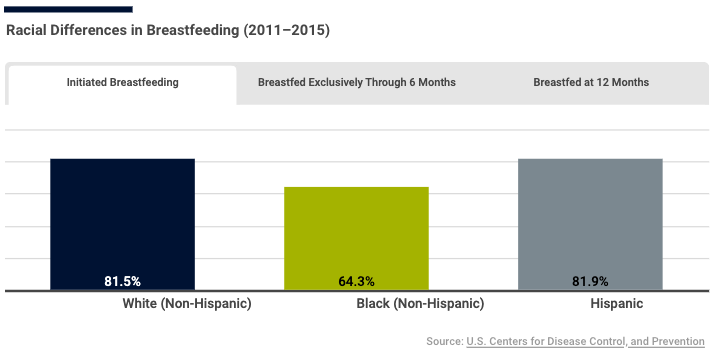

However, breastfeeding rates have historically been lower among African American women compared to white and Latina women. There are many reasons for this gap, including cultural beliefs and preferences, bias among healthcare providers, and even formula marketing practices.

Economic barriers also play a big role. Low-income and low-wage working mothers who cannot afford to take significant time off of work after giving birth, or who work in service jobs that aren't supportive or conducive to pumping, often as a result fail to establish a good breastfeeding practice and meet their breastfeeding goals.

Adding to these barriers is a lack of free professional or peer breastfeeding support in communities of color in Boston. “For people of color, initiation rates are high in hospitals, but once they leave the hospital, the support is not there," Pike says.

Filling the need for breastfeeding support in these communities was at the root of the Boston Breastfeeding Coalition’s inception. The coalition's pop-up baby cafes, hosted Monday through Friday, were launched in the racially and culturally diverse neighborhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan, and have since expanded to the South End and East Boston.

At these support groups, nursing women can build social capital by surrounding themselves with peers who are going through similar experiences, learn about the social and emotional development of their child, access resources to diaper banks and other infant supplies, and work through any nursing concerns with educated and trained counselors.

There are many challenges that mothers and caretakers may face when breastfeeding or attempting to breastfeed. These challenges include babies not being able to latch, pain, mastitis (a common breast infection), and an insufficient or inconsistent milk supply.

For women experiencing any of these issues, the support groups are a “safe haven,” says Bellegarde, who works as a co-facilitator for the groups. “It’s not just a dialogue between the individual and the lactation professional. It’s a community. We have other mothers who can chime in and help even more.”

Creating economic pathways for women

Another aspect of the coalition’s mission is scaling its impact through workforce development and diversity, through a service-learning and leadership program that helps women achieve CLC certification. Some women go on to pursue international board certified lactation consultant (IBCLC) status, a tier above CLC that requires more educational courses and clinical hours and potentially opens a new career pathway.

The scholarship component of the program, funded by Vital Village, offsets the costs of becoming certified as a lactation professional, which can be significant. According to Pike, for CLC courses, training, and exam, it amounts to nearly $1,000. And to become an IBCLC, the exam itself is $500, and requires 500 to 1,000 clinical hours and tuition costs.

The service-learning program also contributes to the diversity of the field. Historically, the field of lactation professionals has been mostly white. In Massachusetts, just a handful of IBCLCs are women of color. By contrast, of the 90 peer scholars Vital Village has collectively trained, 84% are women of color.

Photo: Boston Breastfeeding Coalition members Dominque Bellegarde (left) and Jenny Weaver, at the Mattapan Branch of the Boston Public Library, one of the locations of the coalition's support groups for nursing moms. (Karen Morales)

“People who are CLCs and IBCLCs are mostly white — they look like me,” says Jenny Weaver, a registered nurse and IBCLC who has worked with the Boston Breastfeeding Coalition since it first launched. “But for communities of color in particular, we know people like to get help from others who look like them.”

Indeed, Bellegard says when she went to the hospital for her mastitis after her second pregnancy, the doctor could not easily diagnose it by looking at her skin.

“IBCLCs who can’t speak the language, doesn’t look like them, and shows them only photos of white women can impact the success rate and the ability of a woman of color to feel confident and comfortable to share what's happening in her family life,” says Pike.

There are about 14 peer scholars in the coalition who are currently working on getting to either CLC or IBCLC status, according to Weaver. The program is recognized by the International Board of Lactation Consultant Examiners as a “Recognized Lactation Support Organization,” a designation that qualifies scholars to pursue Pathway 1 in becoming an IBCLC.

“Many of our peer scholars and CLCs within our coalition are hoping to become IBCLCs,” says Pike. CLCs are usually contracted for part-time work at typically $40–50 an hour, but IBCLC status opens the door for full-time work with hospitals or other agencies. “This is an economic pathway for a lot of women in our network and we're supporting them by keeping track of hours and getting the mentorship they need,” says Pike.

Bellegarde says she is very close to taking the exam to become an IBCLC. When she succeeds, she hopes to open her own small consulting business as an IBCLC, giving lectures and becoming an entrepreneur within her community and helping other women.

“To be able to help others and empower them, especially when they're at their lowest and they want to meet their breastfeeding goals... I know how it feels," she says. "I've been there.”

Read the full article